The Price That Owns You

How Crypto Turns Balance Sheets Fragile

This is a discussion about how companies choose to present themselves on their books, and how those choices shape real-world risk and value. We use MicroStrategy ($MSTR) as a case study because its decision to hold bitcoin challenges standard notions of accounting labels and capital structure…

In plain terms, assets are things a company controls that should bring in cash—now or later. Inventory, equipment, buildings.

Liabilities are what the company owes to others. Loans, leases, unpaid bills.

The two categories may appear clear-cut. After all, their distinction is a core principle of accounting. But telling them apart often relies on judgment—and judgment can be twisted to suit a need or desire.

In reality, assets can have liability-like qualities, and liabilities can have asset-like qualities. Seeing them as fluid labels helps us focus on how cash moves—in both good times and bad.

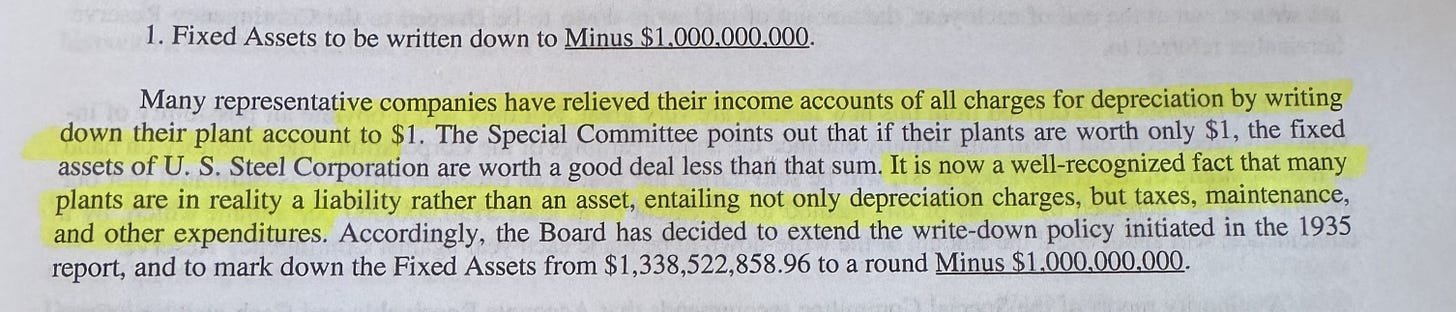

In 1936, Benjamin Graham wrote a satire called U.S. Steel Announces Sweeping Modernization Scheme. In it, a fictitious company “modernizes” not by upgrading mills but by renaming them. He asks: what if a factory is not so much an asset as a burden?

Consider the following: the moment a company builds a plant, it commits to paying property taxes, utilities, and repairs. If customer demand plunges, those costs remain. It can be argued that a factory behaves like debt with a variable coupon: maintenance and operating costs that must be paid whether or not demand is there. In downturns, cash outflows are sticky, while resale value may be negligible.

If a thing creates obligations and resists being turned back into cash, why call it an asset?

The case is intentionally exaggerated, of course, but that’s the point: with the right framing it can sound sensible—and for an illiquid business with high fixed costs, it can even be true. An “asset” can indeed look like a liability whenever it forces spending in the face of sputtering revenue. In those cases, the balance-sheet line item begins to behave like a claim on future cash.

Last year, for example, we took a position in a company called Clearwater Paper but sold out partly because it became clear that paper mill maintenance was too unpredictable—a couple of unplanned outages could have drained cash and pushed results into the red. In effect its assets were more liability-like than, say, the stores of a company like Greggs where maintenance spend is far more discretionary.

So the test of any asset for its “assetness” should be: how reliable are the cash inflows it produces, and how unavoidable are the cash outflows to keep it running?

Now consider the business model of companies like MicroStrategy ($MSTR). It issues shares or debt and uses the money to buy bitcoin, which it books as an asset.

Can we apply the same test here?

Yes, but it’s a little different. Bitcoin produces no cashflows. Its return depends solely on price appreciation. And its “maintenance” cost is dictated by how the position was financed: interest if bought with debt, or opportunity cost if funded with equity.

Nonetheless, we can ask the same question: how reliable is the price appreciation and how unavoidable the cost of financing? In our opinion the answers are, respectively, not dependable at all and very hard to avoid.

What happens when the price of bitcoin drops below the purchase price for an extended period? Soon you have a company that owns a zero-yield asset held at an unrealized loss, financed partly with interest-bearing liabilities.

The common “solution” to such a predicament would be to issue new shares precisely when the stock is cheap. That dilutes shareholders at the worst time, just to steady the balance sheet. That asset is now dictating cash choices—like a factory demanding upkeep in a slump.

Either way, the market price ends up steering capital decisions. And when an asset does that, it starts to look a lot like a liability.

All materials produced by Reveles Research, LLC—whether posted on this site or distributed elsewhere—are supplied solely for information and education. Nothing herein constitutes, or should be construed as, investment, legal, or other professional advice. You should carry out your own analysis and due diligence before acting. Every investment decision ought to reflect your unique financial circumstances, objectives, and tolerance for risk.