The Hershey Company

Taking a bite out of inflation

Consider first the case of your average Joe, who like everyone else hates inflation. Wherever he looks, companies seem to be shamelessly raising prices as if this was part of some concerted effort, a conspiracy even, to deprive him of his hard-earned cash. But standing in line at the grocery store one day, he eyes a Reese’s peanut butter cup on a display shelf. Does he even notice the increase in price of a few cents, which amounts to a negligible part of his overall grocery bill? Unconsciously he yearns for that comforting memory associated with childhood—Halloween nights among friends, swapping candies like rare gems; Easter treasure hunts at large family gatherings. It’s a minor indulgence he can still afford in these hard times.

From an investment standpoint, the most attractive aspect of Hershey’s business is undoubtedly the strength of its brand portfolio. Established by Milton Hershey before the turn of the 20th century, the company has since become a household name in the United States, where it currently derives 88% of its revenues.

Over time, through a series of strategic acquisitions, it has broadened its scope beyond the original chocolate bars and kisses. The company now offers a diverse range of popular treats including Reese’s, Kit Kat bars, Jolly Rancher candies, and Twizzlers. It’s entirely possible that the enduring profitability of these brands stem from their nostalgic associations. It’s a kind of sentimental value which could, in theory, lead to greater pricing power.

It’s also a narrative Michele Buck, CEO of Hershey since 2017, has been trying to sell. “The consumer’s desire for emotional connectivity is [a trend that] is going to remain,” she said on CNBC.1 In another interview with the New York Times, she reflected on her experience working at Kraft for 17 years, and highlighted her success with this kind of marketing approach:

“I had an opportunity to work on Cool Whip, which is a highly profitable business. The question was: How do you sell more? I was able to create a fifth holiday for that brand that they still use today — the flag cake for July Fourth, which was a big new opportunity that drove significant growth.”2

The Retailing Industry

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the food retail sector (hyper-markets, super-markets, convenience stores, etc.) has seen significant consolidation in the last three decades. In 2019, food sales by the 20 largest retailers accounted for 64% of total food sales, more than double the sales value in 1990, at 31%.3

The pandemic further accelerated this trend, prompting a shift in consumer preferences away from in-store purchases, thus benefitting those retailers with the financial means to invest in online platforms, like Walmart and Amazon, by giving them an advantage over regional players. Kroger's proposed acquisition of Albertsons for $24.6 billion, which will result in the creation of the third-largest grocery retailer, is just the latest step in this direction.

At first glance it would seem that the rise of major retailers would disadvantage suppliers / manufacturers like Hershey by shifting the balance of power in marketing channels away from them, given that they must now negotiate with fewer, larger companies. Dominant retailers (especially Walmart) are known to squeeze supplier margins. This is undoubtedly true—power has shifted downstream—but there are benefits to such a relationship, too, as it enables the sale of products in bulk, which in turn allows manufacturers to enjoy scale economies in transaction costs.

Another consequence of industry consolidation has been the rise of the practice of slotting fees. A slotting fee is an upfront payment that a retailer requires from the manufacturer as a precondition for carrying its products, usually paid at the time of signing a supply contract. Slotting fees are now standard practice among national grocery chains, and serve as a way for retailers to ensure that manufacturers share some of the risk associated with potentially unsuccessful products.4

Slotting fees are a financial burden on the manufacturer, but they have also become a powerful moat against smaller rival brands. For these smaller brands, attaining the necessary scale to secure a contract with Kroger or Whole Foods, and pay the upfront fees, is increasingly out of reach. As a result, being acquired by a major supplier who can leverage its manufacturing prowess and distribution networks to scale the product efficiently is often seen as the quickest path to growth.

Viewed through this lens, the rise of sprawling Consumer Packaged Goods (CPG) corporations such as Nestlé, PepsiCo, and Mondelez—each managing an immense range of products under multiple subsidiaries—can be understood as a logical and coherent reaction to this modern competitive environment (in the U.S., especially). In fact, in the absence of smaller competitors, one might argue that these conglomerates have become crucial intermediaries or gate-keepers, connecting retailers to the broader consumer base.

To be sure, Hershey is not yet as sprawling a CPG company as some of its global rivals, with a $40bn market cap versus Nestlé at $301bn, PepsiCo at $231bn, and Mondelez at $99bn. But it is definitely signaling its intent to become one.

In 2017, Michele Buck announced a goal of transforming the company into “an innovative snacking powerhouse.”5 The firm’s strength in generating cash flow from existing brands—she argued in jargon-filled language—allowed it to deploy capital into new areas like salty snacks (more on this below).

Private Labels

The rise of the giant retailer might lead us to conclude that Hershey is at risk of competition from private labels. But history shows that chocolate-makers, in the U.S. at least, have traditionally faced minimal threat from this area, resulting in little margin pressure from lower-cost alternatives. Confectionery, unlike other private label categories, requires “conditioned distribution” (i.e. the use of refrigerated trucks to maintain specific temperature and humidity levels) and involves intensive labor to stock, being small, delicate, low-value items. This logistical challenge is one of the reasons Walmart opts to work with third-party distribution services, such as McClane, instead of handling direct orders themselves.

Here’s Michele Buck on the Q1 2022 earnings call:

We are constantly looking at… how much market share is going to private label, as that has typically also been a predictor of the consumer. We’re fortunate in our category not to have significant private label, but certainly in other categories where that’s present, we do look at that, as well.

She is acknowledging that in times of economic pressure, like inflationary periods, consumers may trade down to less expensive options in the broader CPG market, although this behavior does not directly apply to classic Hershey offerings.

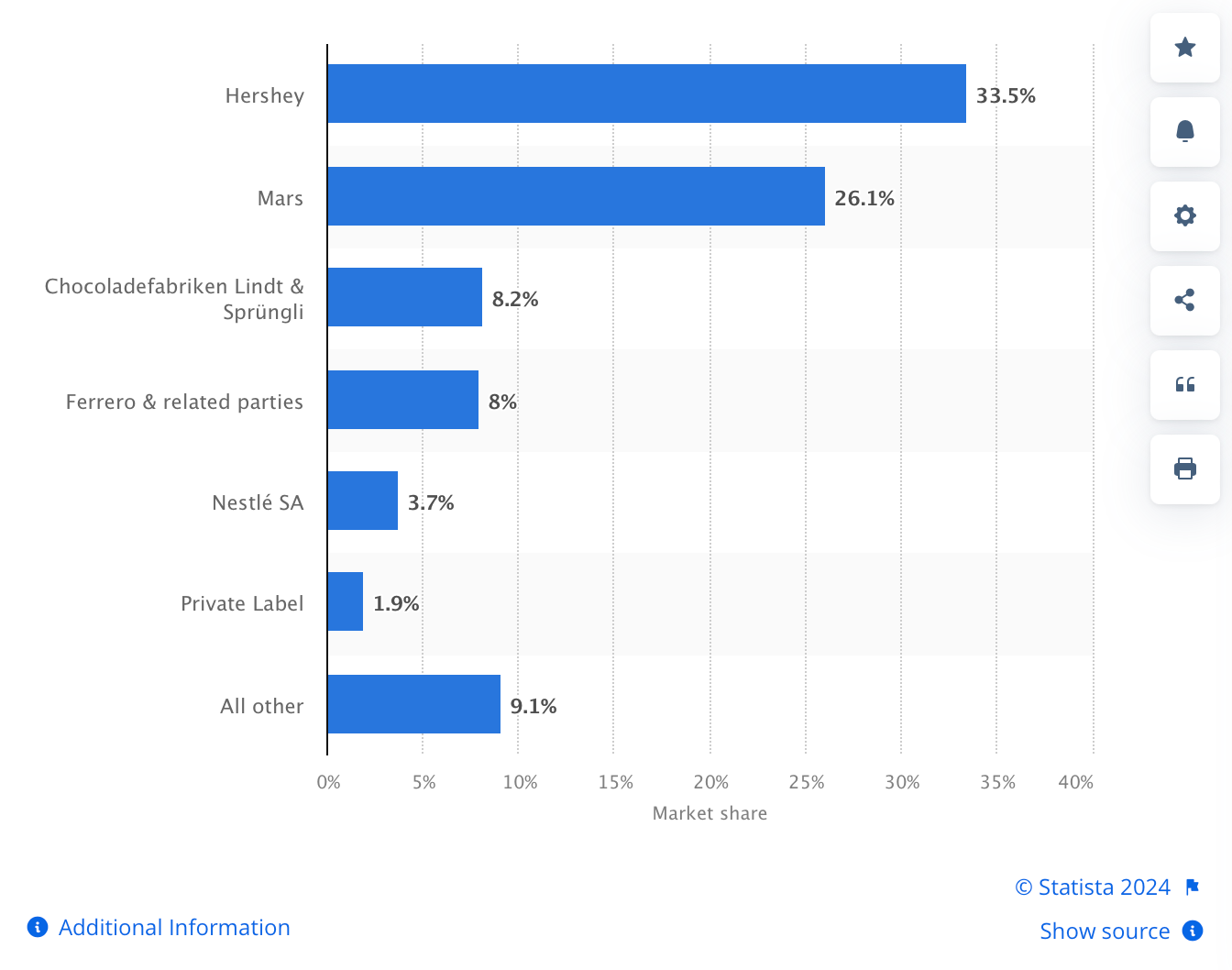

According to Statista, the market share of private labels for chocolate in the United States in 2021 stood at 1.9%.

The Other Competition

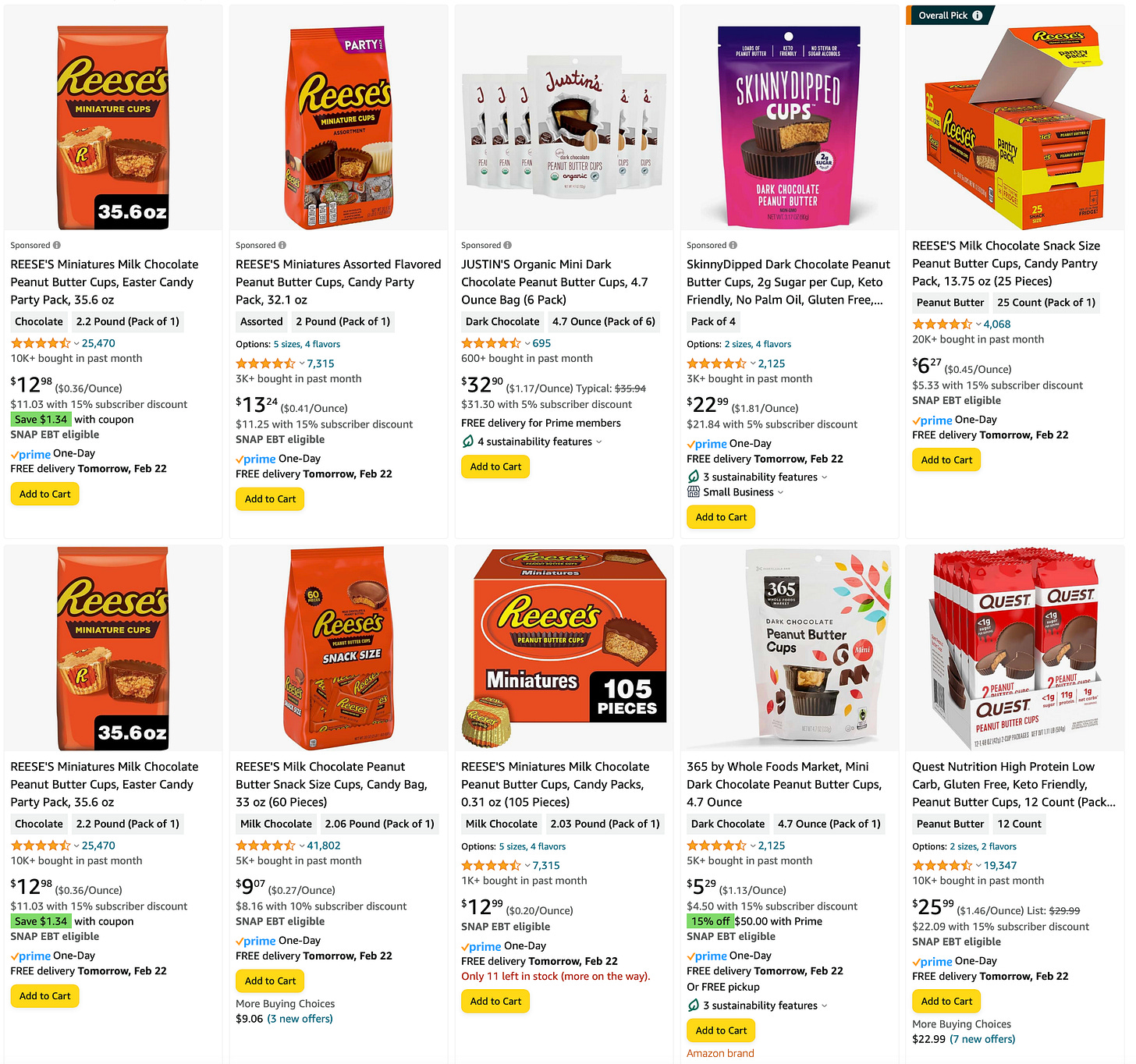

So, where does Hershey face competitive pressure, if not from private labels? A quick search on Amazon for peanut butter cups reveals the extraordinary extent of the cost advantage that Hershey still holds in its main product line:

In the top 10 results we have:

A variety of Reese’s products ranging from $0.25 - $0.45 / ounce

Justin’s at $1.16 / ounce

SkinnyDipped at $1.79 / ounce

365 by Whole Foods at $0.96 / ounce

Quest at $1.46 / ounce

Even the most expensive of Reese’s product comes in at less than half the price of the cheapest competitor: 365 by Whole Foods. Beyond the top 10, I could find no other competitor selling peanut butter cups online for less than $1 / ounce. [Of course, an online search necessarily excludes private labels—other than for Amazon / Whole Foods—which would only be available in stores.]

Here’s Michele Buck again on the same call:

Reese is our biggest brand by far, it’s a couple billion dollars in size, and when it is growing double-digits, as it has been, and has had such a track record of strong growth, that is—that’s where some of the—you know, the biggest rub and the biggest dollar opportunity that we’re focused on.

She seems to imply that Hershey’s outsize reliance on a single brand, even one as successful as Reese, could not only lead to upside opportunity but also downside risk. To put a couple billion dollars in context, in 2022 Reese accounted for 20% of total sales.

Second Business Line

Which brings us back to the rationale for branching out into salty snack categories. Let’s look at a timeline of recent acquisitions:

2015 - Former CEO Bilbrey led the purchase of Krave Jerky, an all-natural brand of premium jerky products, for $218mn (6x Krave’s sales). He’s since acknowledged that the acquisition was a disappointment. Mainstream jerky brands grew much faster than premium, and a glut of brands in the higher-end space squeezed margins. The brand was written down and sold off in 2020.

2016 - Under Bilbrey, Michele Buck, then president of North America division, advocated for the purchase of barkTHINS for an undisclosed amount6. barkTHINS falls into the 'mass premium' category: products of higher quality than standard items but still accessible to a wide range of consumers. It’s a differentiated product with an innovative texture, which I believe fits very nicely within Hershey’s portfolio.

2017 - New CEO Michele Buck pushes for the purchase of Amplify, maker of SkinnyPop, for $1.6bn (reportedly at 4x Amplify’s sales)—marking the biggest acquisition in the company's history. It's somewhat baffling that Hershey would spend so much in a product that is fundamentally composed of just three ingredients (corn, salt, oil) and which appears to have no differentiation, both in terms of the product itself and its manufacturing process. While SkinnyPop might have enjoyed considerable profit margins at the time of acquisition, benefiting from being an early entrant in the market and boosted by heightened demand during lockdown periods, I'm skeptical it does now—or will in the future. When I conducted searches online and in retail stores for competing products, I noticed that private label options were not only cheaper but identical in quality.

2018 - Pirate Brands, maker of Pirate Booty, for $420mn. It has a loyal fan-base.

2019 - OneBrands, maker of “low sugar, high protein nutrition bars”, for $397mn (4x sales)

2021 - Dot’s Homestyle Pretzels for undisclosed sum. (Have never tried it.)

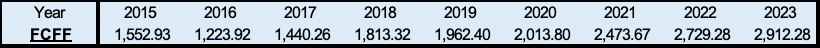

These are large sums. But at least they are being funded by the company’s own free cash flow, and not debt (as net debt / EBITDA has remain relatively constant). To put the sums in context, this was Hershey’s Free Cash Flow to the Firm (FCFF, in millions) over the last few years, more than enough to cover the acquisitions:

While these new brands are expected to drive higher growth, there's a concern about whether it will come at the expense of operating margins due to the inevitable shift in product mix. According to Goldman Sachs, operating margins for the confectionery division stand at 33%, which is significantly higher than the salty snacks division at 17%, and even more so when compared to the international division, which is at a lower 14%.

So far, it hasn’t had any negative impact. It seems Hershey is harnessing the power of its confectionary brands, and leveraging its cost advantage in conditioned distribution to increase its presence in store shelves for salty snacks. The current share price assumes there will be no negative impact going forward (see below).

In another post, it might be useful to look at how Mars and Mondelez are moving into snacks, and PepsiCo is moving into confectionary.

Discounted Cash Flow

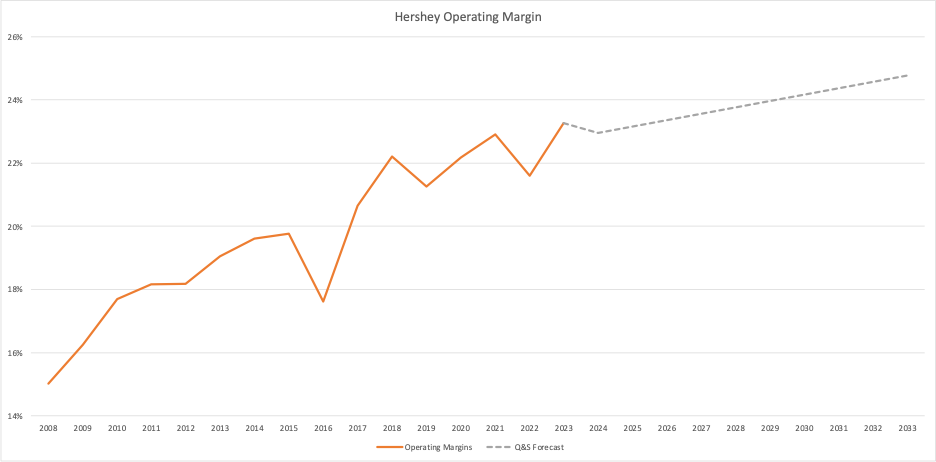

From 2008 to 2023, Hershey managed to increase operating margins from 15% to 23%, demonstrating this capacity to raise prices without significantly impacting demand. Indeed, in 2022 and 2023, when management began breaking out price/volume mix numbers, most of the increase in revenue came from “price realization” at an average of 8%, versus volume increase (i.e. demand), at an average of 1.4%.

Projecting this forward over the next decade, with a conservative trend-line based on the data since 2018, we can expect an operating margin on the order of about 25% by 2033. This projection could be complicated by factors discussed above, namely that any future price increases in confectionery may not sufficiently offset the mix shift towards lower-margin salty snacks. In other words, while the company currently is able to act as a hedge against inflation due to its robust pricing power with its existing portfolio, this might not be the case ten years from now, when snacking becomes a greater part of its business.

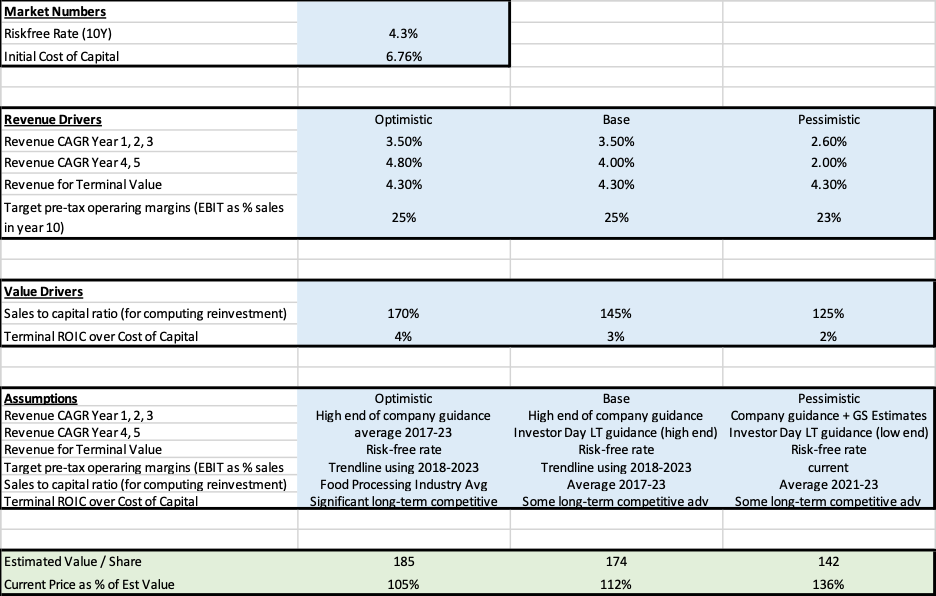

As we can see, the stock price seems to be slightly overvalued at the current $194/share, even when using optimistic assumptions.

Conclusion (and a short note on GLP-1)

Our current stance is one of cautious optimism towards Hershey's stock. While we are buying it at the current price as an inflationary hedge, we would be more inclined to increase our position should the price drop to $180, given the potential pressure that the company's expanding portfolio might have on margins.

Notably, while the DCF analysis suggests that the stock might be overvalued, its EV / EBITDA ratio is currently about 10% lower than its historical average. This could be attributed to market concerns over the impact of GLP-1 drugs on consumption. Based on personal experience, I can attest to the drug’s groundbreaking ability to reduce appetite—for those seeking to reduce their appetite. The point is that I don’t believe most people want to. Eating is not just a necessity but also a source of enjoyment. The real issue lies not in the efficacy of GLP-1 in reducing cravings—which indeed it does, brilliantly—but rather in the intrinsic human desire for the pleasure of eating, making it difficult to embrace such alternatives consistently over the long term. Another way to think about it is: imagine there’s a world in which a pill exists that reduces our dependence on social media. Would we take it? Maybe for a while. But only for a while.

The content provided by Quits & Starts, including all materials on this website, in the newsletter, and in any other communication from its author, is strictly for informational and educational purposes. It is not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, investment, legal, or any other type of advice. Readers are encouraged to conduct their own research and due diligence. It's important to remember that investment decisions should be tailored to an individual's specific financial situation, goals, and risk tolerance.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/10/business/michele-buck-hershey-corner-office.html

https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/105558/err-314.pdf?v=1526.4

http://tinyurl.com/4thatnm9

http://tinyurl.com/4t9nxevm

“In 2016, the business is forecast to generate sales in the range of $65 million to $75 million.”

http://tinyurl.com/bddmr2w5