The Hidden Price of Trade Deficits

Foreign Investment Isn’t Free—It’s a Claim on Future American Prosperity

I wrote a tweet about an article and it got some attention, so I decided to write a wonky post about it.

The article I read was this:

Anyone watching the news, or reading headlines like this, might be inclined to understand that investments into the U.S. are good and that they “erase” trade deficits. That is far from the truth.

When the U.S. runs a trade deficit, it means the country is importing more than it exports—so, more dollars are going out to other countries (e.g., paying for goods from China, oil from the UAE, etc.).

But those dollars don’t just disappear. Foreign countries that receive U.S. dollars from selling goods to Americans often reinvest those dollars back into the U.S. This can be through buying U.S. Treasury bonds, real estate, companies, or other investments—like the $1.4 trillion investment from the UAE mentioned.1

So, when Trump (or anyone) celebrates foreign investment, they’re essentially celebrating the return of dollars that originally flowed out due to trade deficits. It’s a closed loop: the more dollars that flow out for goods and services, the more that flow back in as investment.

The key economic principle:

Capital account surplus = current account (trade) deficit.

You can’t have one without the other in a country like the U.S. that has a floating currency. If you want to eliminate deficits you have to suppress foreign investment, and vice versa. They are quite literally two sides of the same coin.

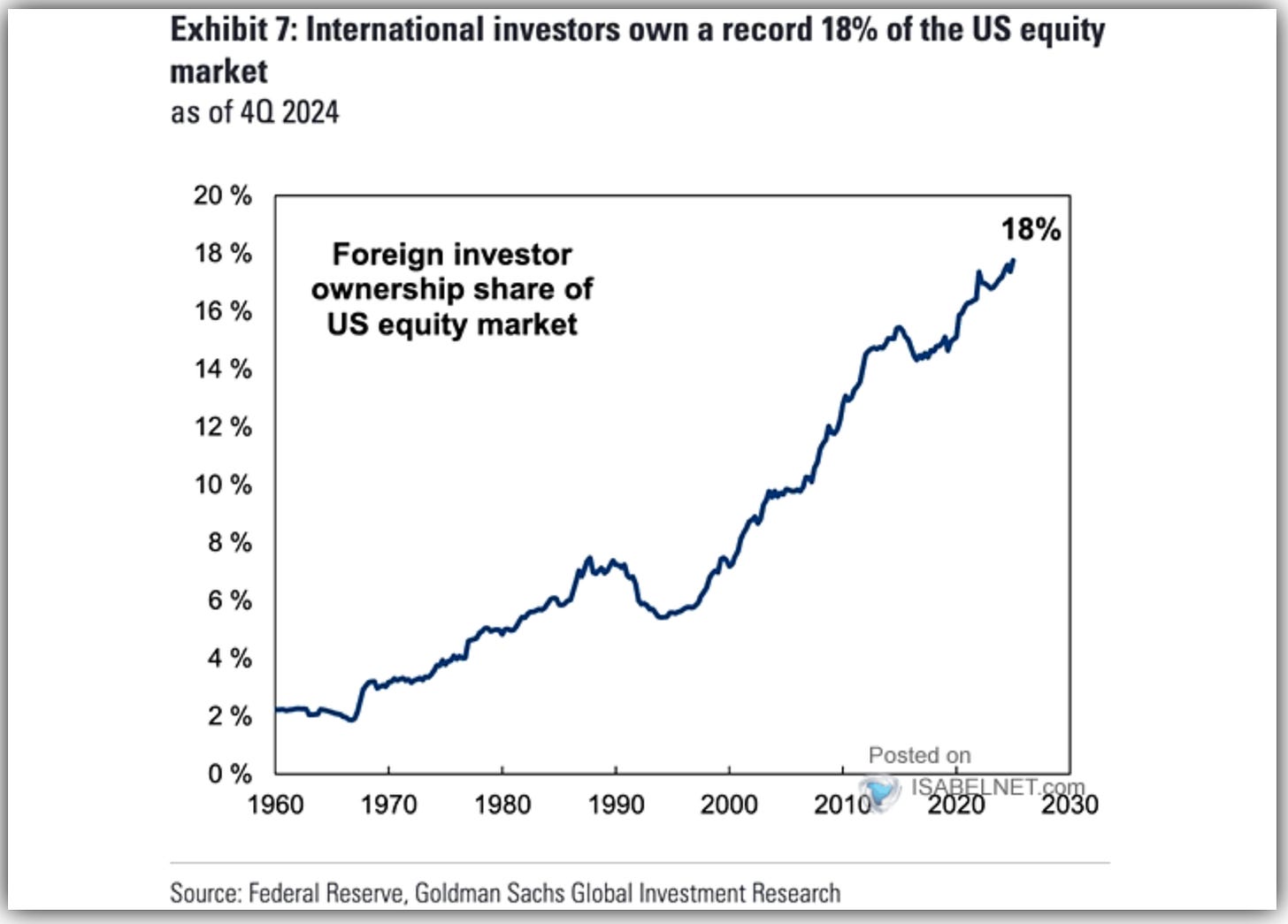

At first glance, the influx of foreign capital—whether funneled into U.S. businesses, Treasury bonds, or prime real estate—looks like a good thing but in practice it shifts wealth abroad as overseas investors steadily claim a larger share of America’s productive assets, property, and future income streams.

We, at Reveles, have differing opinions on the effectiveness of tariffs (Patrick is less sanguine) but we do agree that for them to work, foreign investment into the U.S. in all its forms needs to be suppressed.

I read an analogy from someone on X trying to illustrate the benefits of free trade:

“I have a 100% trade deficit with the lady that irons my suits. She offers something way more efficiently and at a much better price than I can do myself. And in exchange, I spend the time I would otherwise be wasting on pressing my suits offering financial services at 1,000x the hourly GDP rate as I paid her to afford me this time. Am I getting ripped off by her? Should I start steaming my own suits instead of offering financial services? Would that make me better off? Would I be richer because of it?”

The analogy is great—but it doesn’t go far enough.

What is really happening is that with every payment you're giving her, she's simultaneously purchasing a claim on your future earnings-like buying a share of your future productivity. You're not just exchanging money for ironing services; you're implicitly promising a future return-either by borrowing (Treasuries) or allowing her to invest in your future success (US equity market, real estate).

It’s not unlike a company that, say, wants to undertake a large capex project—such as building a new factory. It can either self-fund, maintaining full control and ownership, or raise external funding through debt or equity. Borrowing means committing future earnings to repay investors, while selling equity means giving away partial ownership and future profits.

Over time, servicing these obligations can become so burdensome—consuming significant cash flow—that it reduces the company’s ability to reinvest in its own growth and innovation. This creates a downward spiral: the more the company depends on external investors, the heavier its future payments become, further limiting internal investment and growth opportunities.

Similarly, countries running persistent trade deficits exchange future economic prosperity for immediate funding. Over time, they risk becoming overly reliant on external capital, effectively handing over increasing claims on their economic future to the rest of the world.

In sum: deficits are a wealth transfer abroad—they are detrimental to the country’s future prosperity if left unchecked for too long.2

Example: When an American company purchases electronics from Japan, it pays the Japanese exporter in U.S. dollars. The exporter then exchanges those dollars for Japanese yen at a local bank, like MUFG, since yen is required to operate domestically. MUFG Bank now holds these dollars but doesn’t let them sit idle—it either sells them on currency markets or invests directly in dollar-denominated assets like U.S. Treasury bonds. Alternatively, MUFG might sell these dollars to Japan’s central bank, which similarly invests them back into U.S. assets, bolstering Japan’s foreign exchange reserves.

Now, it can be argued that investments into U.S. manufacturing by foreign companies do help reduce trade deficits because they shift part of the production process domestically, keeping more dollars circulating inside the U.S. economy through wages, local suppliers, and taxes.

However, the bulk value of many goods—particularly high-tech components, raw materials, or specialized parts—still tends to be imported from abroad, maintaining a significant outflow of dollars. Thus, while local manufacturing investments mitigate the deficit by retaining a portion of economic activity domestically, the core trade imbalance often persists because substantial inputs and components continue to come from overseas.